Francisco Messa was born on 20th March 1728 in the outlying district of Castillo de San Felipe (Raval del Castell de Sant Felip, in Catalan), a unique Minorcan town which during the 18th century shared considerable similarities with Gibraltar, in a family of Extremaduran origin that had arrived in the island in the middle half of the previous century (1). As had previously been the case with his brother Rafael, Francisco Messa also entered the Augustinian Monastery of Socors de Ciutadella on 2nd March 1744. Here he lived through the vicissitudes of the so-called ‘century of dominations’ of Minorca, when the sovereignty of that coveted Mediterranean enclave was transferred from one state to another, i.e. Great Britain on three occasions (1708/1713 to 1756; 1763 to 1782, and 1798 to 1802), France (1756 to 1763) and Spain (1782 to 1798, and definitely from 1802).

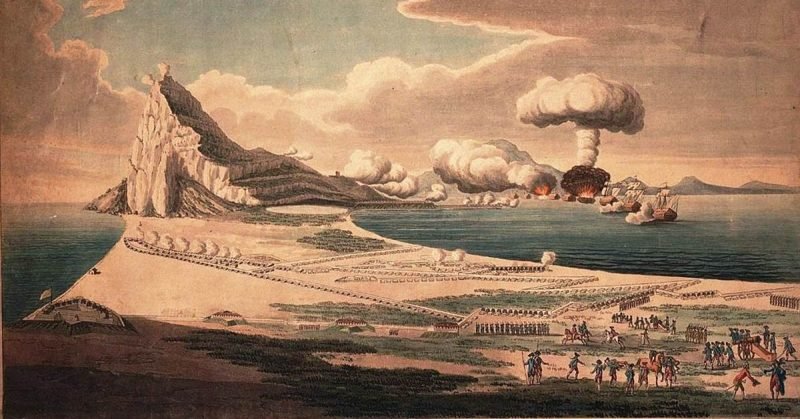

In the 1770s, Francisco Messa again decided to follow the example of his brother Rafael, who had left Minorca in 1771 in order to make himself responsible for the Parish of Saint Mary the Crowned in Gibraltar. However, after two years in that city, he took ill and wrote to his brother asking him to come ‘to assist, console and help’ him. Francisco Messa, with the permission of the respective governors of Gibraltar and Minorca, Edward Cornwallis and James Johnston, left his monastery of Ciutadella in order to travel as quickly as possible towards the straits. However, when he arrived, he learnt that his brother had already died. Lord Cornwallis, taking advantage of the situation that had been created, requested that Francisco should take over the responsibility for the Roman Catholic Church in Gibraltar and this was duly taken up by him. This was the beginning of a long vicariate that lasted for almost twenty years in which Francisco Messa lived through the frequent internal squabblings of the Gibraltarian Roman Catholic community, together with the cruelty of the Great Siege, in which he suffered personally. This siege, from 16th June 1779 to 12th March 1783, was the last Spanish attempt to occupy the fortress by force of arms, resulting in a four-year long nightmare both for the soldiers and the besieged civilians, bearing in mind the bombardment and blockade by land and sea which was both intense and unsuccessful.

Charles Caruana, in his book The Rock Under a Cloud (1990), noted that Francisco Messa’s diary was the only extant account by a civilian of the events of the Great Siege. It was recovered by the said Bishop of Gibraltar from the last pages of a primer (libro de párvulos) of the parish (1777-1805) and describes the horrors that were experienced by the chaplain and his church, together with the six hundred civilians who remained in the city, during the bombardment of 1781. This chronicle, written in the first person, in fact contains a considerable number of examples of the lexical and phonetic characteristics of the Catalan language spoken by Minorcans who passed through or settled in Gibraltar during the course of the century (2). It contains valuable details from inside the Garrison regarding the siege, the principal military actions, the arrival of convoys and provisions, the price of and scarcity of food and the settlement of the inhabitants in the extreme south of the Rock, having moved there because of the incessant attacks by the Franco-Spanish batteries.

Messa actually describes how he was able to transport, without any help of the members of the Junta of Elders, some of the relics and treasures of the parish to the caves and encampments in the area of Windmill Hill and Hardy Town, before they were consumed by fire. Caruana pointed out that, following the end of the Great Siege, the behaviour of this ‘Minorcan hero’, so obsessed with saving the ecclesiastical valuables, was not in any way out of the ordinary:

“The Junta was, of course, anxious to re-establish its former position. It asked the priest to hand over to them the valuables still in his possession. Father Messa refused on the grounds that he had risked his life to save these things when he had been left all alone to witness their almost certain destruction at the time of the bombardment. The Junta, without more ado, went to complain to the Governor, and the latter took their side. The parish priest, now old, weary and ill, was censured and kept under house arrest until he surrendered the valuables to the Junta.”(3)

On 3rd June 1792, the Genoese assistant priest, Pietro Raymundo, made the following entry in the Book of Burials of the church:

“With the most solemn of rites, I interred in the church the Most Reverend Friar Francisco Messa, Augustinian Religious, Doctor of Theology, Priest of this Parish of Saint Mary the Crowned and Vicar of the Roman Catholics of this Garrison and City of Gibraltar… He had received the holy oils. His illness, which had left him paralysed, did not allow for more time; and he was buried with great pomp and public solemnity. The funeral costs were paid by the Church. He ran this Parish of Our Lady the Crowned for 19 years and 2 months, and died at the age of sixty-four.”

Apart from leaving us his interesting and unique personal diary, Francisco Messa also contributed in his own way to the history of the Rock because in 1774, in his name, the Anglo-Minorcan Lieutenant-General Robert Boyd made a request to the Roman Curia to have the Parish of Gibraltar dissociated from the Diocese of Cádiz, a petition which was conceded in the summer of 1792… shortly after the death of the chaplain from the Arraval de San Felipe.

Notes on the events which took place during the siege of this city in 1779 (4)

On the 21st of June of the said year, entry into this city from Spain was closed and even before that, the Commander in San Roque had ordered that all subjects of the King of Great Britain should immediately leave the Campo de Gibraltar and withdraw into the city. Unfortunately, the case arose of some young girls who were staying in San Roque suffering from the pox, and those caring for them were obliged to leave, and the Governor of this city not wishing the pox to be spread, made them remain in the market gardens at Land Port, until they were completely recovered. In the afternoon and during the night of the 4th July, some English corsairs captured thirteen or fourteen prize ships, which were laden with provisions for Spain; sailing with them were some jabejes (5), which withdrew with some other vessels to Seuta (6). During the afternoon, they engaged battle with the English corsairs, even under the batteries of Europa Point, in such a manner that one of these shot some of their cannon against one of the xebecs. On the 13th, the Spanish squadron of xebecs with two ships of the line and two frigates appeared and blockaded the Bay, thus impeding the entry of most provisions; notwithstanding, some Portuguese and Moorish vessels laden with oxen and other goods were able to get in. On the feast day of Saint Anne, 26th July, they commenced setting up military tents in the Campo and disembarking war munitions and increasing them on a daily basis.

30th August. During the night, the secretary John Ralingh (7) came to my house and informed me that by order of the Governor Aliod (8), the Catholic church was to be requisitioned for use as a store for naval provisions, to which I replied that I was already aware of this, but that I thought that the Governor would not wish to deprive us of the place where we performed our sacrifices and had our holy sacraments. He replied that this was not the case, and that the intention was only to take over an area near the entrance to the said church, and that the decision was up to the commissioner, Mester Daevies (9). I respectfully requested that I be notified, before they went to view the church, so that I could point out the most appropriate sites for the said project. The following day, the said secretary and Mr. Davies went to the church, about which I had been notified and then went there, and on my way I met up with the said gentlemen in the street, who informed me that they were on the way to my house to speak to me. I asked them if they wished to accompany me to the church, to which they agreed and we made our way there. I showed them the Capilla de los Ierros (10) and asked them whether this would be sufficient for their needs, but the commissioner replied that this was not good at all. I then showed them the aisles on the sides of the choir and the area behind it, and he did not feel that that was sufficient. I then pointed to the line of the first columns and seeing that it was not enough, extended the area up to the second columns and even that did not satisfy him. The secretary then remarked that it appeared that not even the entire church would be large enough for Mr. Davies, and seeing this, I then included the area up to the three main altars. At this point, we began to discuss what would satisfy the Catholics and the King. I proposed it would always be better to agree on what would be mutually beneficial and with that we parted.

That same afternoon, the admiral came to look at the church; I had been notified, so I went there. This gentleman agreed that a partition should be set up from the entrance to the column where the pulpit stood, and from there straight to the wall of the Soledad (11), and thus it was done and we were able to enter our church by its main door and they having access to their store by the other entrance, where the well was located. And we were quite content, as we were concerned that they would have taken over the church entirely, for more unbecoming purposes, as happened in the other siege, when it was completely taken over as a hospital, as recounted by the older inhabitants; and I was further assured that it would only be for a short period of time. On 3rd September, the said area of the church had been emptied and work commenced to set up the partition, and we were no longer allowed access into that part and it began to be used by the commissioner.

On the 12th September of that year of 1779, at approximately five thirty in the morning, the English batteries, located in the highest point of the Rock, commenced their firing and continued to do so all that day in order to impede the work being carried out by the Spaniards on that part of the Lines. And, in fact, they did stop them substantially, as on previous days one could see the coming and going of laden and empty carts which were making their way from the Campo to the Lines and vice versa. This did not happen after that day, on which we celebrated El Dulcíssimo Nombre de María (12), when there was a commotion among the families resident in the area around the Water Port, who fearing that the Spaniards would return fire, decided to make their way to la puerta del sur (13) with all their goods. But the Spaniards did not fire a single shot, neither on that day nor even during the following week; the English continued to fire and bombard them, although at longer intervals. During that week, the cobble stones were removed from Eriston (14) and Real (15) up to la plasuleta del quartel de las Monjas (16). The bell tower of the Convento de la Merced (17) was also dismantled. Many of the Catholics and Jews began that week to build wooden houses in that part of the Rock near to el jardín del Coronel Grin (18) in order to remove there their goods and possessions.

Day 26 of the said month of September of the said year of 1779, at ten in the morning, being a Sunday, Captain Yveli (19), engineer, met me in the street at the entrance to my house (and I think that he came there), and spoke to me in English. Although I understood him, but not wishing to depend on my limited grasp of the English language, I told him that my brother-in-law, the carpenter Joseph Serra, who understood English very well and would be able to clearly explain what he wanted to tell me, was in my house. Consequently, this was done and both of us being there with my said brother-in-law, the said captain gave his account and my brother-in-law then told me that the gentleman was informing me that by order of the Governor Alivod (8), the bell tower of the Catholic church had to be dismantled, because it was of great assistance to the Spaniards in the Lines. And that it had to be dismantled up to the level where the bells were rung; I replied whether it was possible to start dismantling only up to the openings where the bells were hung and he replied that it would not be possible. First of all, it was necessary for the bells to be brought down and that they would then work out a way to hung them up lower down. To which I replied that if it were so necessary, I would not be able to object, but hoped that once the siege was over, that these would be restored to where they had been originally, and he replied that that would certainly be the case. And thus we parted. Some days went by and nothing happened, so that I began to think that it would not be carried out, when on 6th October, my brother-in-law came to tell me that the order had already been given to dismantle the belfry and to demolish it as quickly as possible. On the morning when I went to the church, I found the engineers already there setting up the scaffolding for this undertaking, so that by the 7th of the said month and year, on getting up from bed, the first and sad view that I had was of a soldier removing the first stone, which was the one at the very top. And everything was done so quickly that by the 13th of the month, that part of the tower containing the bells and clock, just under the first level, had been dismantled. In December, they began to reconstruct the place to set up the clock, lower down than where it had been originally and they are still continuing the works.

On the 26th December, día de San Juan (20), there was a great storm and a lot of rain, and the inhabitants having such a scarcity of firewood for their kitchens, the waves brought so much wood from the coast of Spain to below the fortification walls, that we had enough until the next convoy arrived. That was the very first day that the Spaniards fired some of their guns against the batteries in the Land Port, which I believe were not more than five, and Bartholome Galle, one of the companions of the gardeners of Juan Baptista Viale, brought to my house a bomb that had fallen into his market garden, weighing about 26 pounds. On 12th January of the present year, the Spaniards fired some shots at the Water Port and Land Port, and a shot passed over the walls of the Land Port and hit the roof of Antonio Quartin, which happened to be unoccupied, and only made two holes in the roof and fell in the street near the house of the carpenter, Mr. Boid (21).

On the 26th January of the present year of 1780, foodstuffs were already so expensive that bacon cost 6 silver reales per pound, goat’s meat 4 reales, beef also 4 reales. There was no lack of customers; indeed they were more determined to carry on buying, and the cheapest chickens were being bought at 2 duros, and there were some that were sold at 5 duros. Eggs cost a silver real each, butter 4 reales, oil 4 silver reales the quart and was not even of a very good quality; bread was so scarce, that only one of the bakeries sold it and this was very rationed. It was on this day, that part of the English convoy began to arrive, escorted by 26 ships of the line and some frigates that had captured five Spanish ships of the line and also taken prisoner was the Commander of the Squadron, Don Juan Langara, who had received three insignificant wounds. On board of one of the English ships of the line was His Royal Highness, Prince William, third son of the King of England, a few months short of fourteen, serving as a guardia marina (22). He walked down the Main Street with the two governors, Aliot (8) and Boyd, and two admirals and other gentlemen who accompanied them. He wished to enter our church and did so, it being empty at the time, and being notified, I went there and found them by the entrance and offered to show them the treasures of the church, but they replied that they had already seen the images. And so they departed and I accompanied them down the Main Street and along the walls of the Land Port and even near to the Lieutenant Governor’s house and seeing that they were going to have lunch, I left them and came home.

With their arrival, there was such a large quantity of biscuits and flour that the biscuits were sold as at little as 4 quarts the pound, and we were well supplied with great abundance for a time.

On the first day of March, I was asked for the use of the Sacristy and Capilla de los Hierros (10) in order to store the flour, and it was requisitioned that same day as there were no other stores to place it in. On the 26th, Easter Day, the clock-winder asked to block up the door leading to the belfry and to open another one outside the cloisters of the church. I put the request to the governor that same day, who did not offer a reply, although the next day he sent the Quarter Master General to see me and to tell me that the governor had given permission to have the said door opened out to the street and that I would have the key to it so that I could be able to go up to the belfry whenever I wanted.

After the clock had been repaired, they mounted the principal bell to the right of the clock tower, making an opening in order to pass a rope so as to ring it and we began to ring the said bell as from the 27th of April of that year of 1780.

On the 7th June of the present year of 1780, between one and two in the morning, the Spaniards very slyly conducted nine fire ships to the New Mole, judging by the direction that they were taking, in order to set it on fire. However, being discovered by the English launches that were on guard some distance from the mole, the latter commenced firing and also the batteries and ships that were able to do so. The currents being favourable towards the mole, they were diverted and the majority of the fire ships ended up beyond the said mole and some of them did not reach it as they had been fired upon (23) when they reached the middle of the bay. One of the said fire ships was almost at the entrance to the mole, and the English launches managed to steer it towards the walls in front of the Naval Hospital. This vessel was so large that it alone could have set alight the whole mole, as it was made up of so much combustible material that, despite the amount of sea water poured on it by the sailors, it continued giving off smoke for more than 40 hours. On this occasion, the English sailors carried out their duties so well, that seven of them suffered burns to their hands and backs and had to be taken to hospital. It is said that the naval commander has rewarded them with the equivalent value of the burnt ships, that is, with whatever could be salvaged. It is reported that after three hours, one of the fire ships which had sailed past Europa Point, because of the direction of the wind, ended up near Estepona.

On the 7th of October of the said year, on the day of Nuestra Señora del Rosario (24), in the morning, it was perceived that a wall had been built of brushwood near to the market gardens of the City of Gibraltar, which seemed to be the commencement of a battery for 7 or 8 cannons. During that same night, the shacks and waterwheels in the gardens were set on fire by the Spaniards, and found near the fencing was some equipment which appeared to be for the purpose of burning the said fencing, but nothing happened. At the beginning of the summer of the present year, the Spaniards impeded our communication with Barbary so that, during the whole of this summer, we have only seen the arrival of just two launches with the consul’s mail. We have had no other provisions other than those brought in by some ships from Minorca and a Danish doguer (25) which was forced into the harbour by the English launches. Today the 21st day of October of this same year, a ship has come in from Argel (26). After several days, we received some provisions by means of two Minorcan bastimento vessels (27) and also an English one that came from London laden with butter, cheese porter and other kinds of goods which are so necessary both for the English troops as for the inhabitants.

A few days later, there appeared a ship that had sailed from Lapuente (28) having on board the English consul who had been in Barbary accompanied by the Dutch consul, Don Francisco Butler, and all the British subjects resident in Tangier, all of whom had been expelled from Barbary by order of the Sultan of Morocco. The reason was that the Spaniards had bought the franchise for the use of the ports of Tangier and Tetuan, and this resulted in our being deprived of the imports that used to arrive from Barbary; the rest of the year we continued with great scarcity of food. Towards the end of the year, permission was granted to the inhabitants and everybody else to construct on the Rock, some distance from the market garden of Colonel Gren (18). The more fearful ones, who actually ended up being the most fortunate, built some wooden shacks where they secured most of their belongings; but I was assured by the elders who had experienced the previous siege, that the shots and bombs could not reach up to our church. I therefore put all my confidence in the shelter provided by the church and there I stored some of my more fragile furniture, such as mirrors and pictures, with the hope of being able to transfer the remainder to the said church; I continued to remain calm, but this led to very unfortunate consequences.

Following the entry into the bay of a large convoy of a numerous English fleet and which had disembarked many of the provisions, it happened that on the 12th of April of the year of the Lord 1781, the Spanish batteries began firing so fiercely that it caused a great panic in all of us, especially the inhabitants of so many nationalities in the city. So that mothers grabbed their younger children in their arms and dragged the others, made their way, crying, away from the imminent danger towards the South Port; the fathers did the same, taking nothing with them apart from what they were wearing. At the time, I was celebrating the service of the Last Supper and was singing the High Mass, being left almost on my own in the church; nevertheless, I was able to finish the sacred ceremony of that day with high spirits and remained calm in the company of a few devout parishioners.

Having completed the solemnities, I returned home in order to have some refreshments and later, together with my household, I went to take refuge in the church together with some others, although in fact there were very few devotees, and we sang Matins. However, gradually, they all departed just leaving me and my sacristan, Juan Moreno, and those of my household on our own and there we remained on this most solemn and terrible day, all through the night with His Divine Majesty exposed until 8 o’clock of the following day, which was Good Friday. On the previous day and during the night, not one shell or bomb fell inside the church, although many fell in the surrounding area. However, on the morning of Good Friday, being with all the members of my household and the sacristan, crouching and pressed by the column of the Chapel of Saint Anthony, a shell came in and hit the floor about two yards away from us. We were so shocked that two gentlemen who had come in to check whether we were alive and well, having observed the blow of the shell, run away without even taking their leave. At that point, pitying the tearful pleas of my sister, the sobbing of my nephews and nieces, who were all so young, and thinking conscientiously that it was neither right nor prudent to have His Divine Majesty exposed any longer, I decided to cut short the celebrations of the sacred ceremonies of the Good Friday and to consume the Blessed Sacrament, which had been our only refuge during the previous day and night, as the sacristan and I had experienced. Once these celebrations had been completed, we removed as much of the silver items as we could into the sacristy. And I decided to depart from this place of constant danger, with my household, and so I put this into practice, leaving the sacristan as caretaker of the church, and as he was a young and single man he agreed to remain there in charge.

The following day, not wishing to risk danger any longer, the sacristan and I quickly removed the ciborium with the consecrated Hosts, the reserved Blessed Sacrament and the Holy Oils for the sick and those for baptisms. And leaving the silver objects locked up in the sacristy and others in boxes and chests and several set up with their respective images, the bombardment became so intolerable that the church had to be left completely unattended, apart from an old sick Genoese who stayed behind in order to look after the building, which decision distressed me terribly. I took the Blessed Sacrament and the said sacred items to Ambrosio Xitxon’s (29) hut, the same who had taken in my family during our escape. There, with tears in my eyes, which I could not stem, I placed the sacred container on a presentable mahogany table, covered with very clean altar cloths. It remained there continuously lit by a lamp, being our best companion day and night until we were able to construct a small shed in a safer location, as I will explain later.

On Easter Sunday, thinking about the huge collection of sacred images and precious articles which was on the verge of being lost and these being the responsibility of the wardens and Junta of Elders of the church and of the Confraternities of Nuestra Señora del Rosario (24), of Nuestra Señora de Europa (30) and of the Blessed Sacrament, I sent a message to all of them via my sacristan. In it, I exhorted them exhaustively to safeguard the belongings of the church which were in their care, and all of them replied that they could not safeguard their own property, and that they would have enough trouble saving their own property and they further added that anyone who felt they should, could safeguard the church property.

Therefore, considering the great danger that all the treasure of the abandoned church was in, I decided to go in person to try to save whatever I could. The following day, inspired with great zeal and confiding in Almighty God, having searched for other members of our faith and not having found any wanting to accompany me, not even my assistant or sacristan, I looked for and found with great difficulty two English soldiers (as others were giving them half of whatever they salvaged). The soldiers, carrying a stretcher, came with me to the church and I entered the sacristy and found that all the silver objects that we had taken there on Good Friday, those that had been used especially for the procession of Holy Thursday, such as the cross, processional candlesticks and lanterns, were all broken and buried under the rubble which had fallen from the ceiling.

Nevertheless, the soldiers and I removed from under the rubble as many of the pieces and parts of them as we could and placed them on the stretcher and noticing that the tabernacle, or what is termed the monstrance, was still set up on the altar, we lowered it with great difficulty and placed it on the same stretcher, which could not hold anything else. And going out of the church to see whether there was anybody else who could carry something else of what still remained, I found a young man with a donkey who had been sent by my assistant. So opening the cupboards, I took the most precious items and loading them on the donkey, we made our way out of the city, when I saw another soldier who volunteered to carry anything else that I had and, accepting his offer, I returned once again to the sacristy and taking the most valuable chasubles, I tied them up in a bundle and placed them on the soldier’s back with much haste, because the bombardment was increasing. And going out of the church door, the said soldier demanded a guinea for his services, and seeing that he was asking too much, I removed the bundle that he was carrying and loaded it on my own shoulders. With this heavy load and pursued by the shells and bombs, and concerned about the soldiers who were transporting the silver articles, whom I had lost sight of, I made my way to the Puerta Nueba (13).

There I found the soldiers with the silver and the young man with the donkey and its load, who had been prevented by the sentries from continuing on their way because the officer in charge wanted to know who the owner of such valuables was. I went in to speak to the officer, who then let us proceed, but having seen such a great quantity of silver, he wanted to make me go back to the Palace (31) in order to obtain a licence from the governor. But, having explained to him the perils which I had been exposed to and which he wanted me to undergo once more, he finally gave me permission to pass.

Then I was able to place the bundle with the chasubles on top of the stretcher and we arrived ever so tired and leaving the Monstrance in the house of the Reverend Father Raymundo’s mother. My assistant and I took all the rest to a tent which I had managed to have set up by some Minorcan sailors who had contributed a sail together with another one that we had bought from the engineer, Thomas Esqiner (32). And all that night and part of the next day, the silver articles remained quite exposed, and having no chests where to put them, I availed myself of the offer made by Mr. Carbone, a Roman Catholic inhabitant, who lent me two barrels reinforced with iron bands. I disassembled the larger pieces and once dismantled, I packed all that had been salvaged, half in each barrel, and on top I placed the books that my brother-in-law and some soldiers had also been able to save. There they remained, until seeing that the shells and bombs from the Campo and the gunboats were endangering our lives, I determined to search for a dwelling or hut where I could live alone with the rest of my household. However, not being able to find any, and seeing that we were so exposed in the shelter that we occupied, as there were more than forty persons of all sexes and classes, I determined to remove my tent to a safer spot.

In this manner we remained for the rest of the month of April of that year, suffering almost every day at dawn from the destruction caused by the gunboats, which forced the families to abandon their tents and huts and flee up the Rock and also to the llano de los molinos de viento (33). I myself stayed in the area of my tent and hut, so as not to abandon the Blessed Sacrament and other valuables, and on one particular morning, taking refuge beside a mere wall, I was notified of the arrival of the said gunboats. As I was dressing rapidly, a bullet hit just below my tent, and without finishing dressing, I also fled with the rest up to the Windmill Hill.

These circumstances urged me to change the site of my tent, and whilst my brother-in-law, Joseph Serra, with the help of well paid soldiers and other men, busied himself with saving some of our valuables and vestments from the church, I, with my own hands, levelled a plain under the rock which is on the right, in the area in front of the entrance to Windmill Hill. With the assistance of the said Ambrosio Xitxon (29), who lent me the poles, we erected a rather large tent which, however, did not have an entrance. There we transferred all the articles that had been saved, leaving the Blessed Sacrament under lock and key in the said Xitxon’s (29) tent, the latter nonetheless making himself responsible to take care of it, with my visiting it very frequently every day.

The Very Excellent Governor, following the onset of the bombardment by the Spanish batteries, seeing the population dispersed all over the Rock without any proper habitation, there being only thirteen or fourteen wooden huts which the better prepared had built, gave orders for tents to be issued to all the inhabitants who did not have their own tents or sheds. These tents had belonged to the three or four regiments that had been camped near to Hardi Town (34) or Bleck Town (35), and this decision helped the poor enormously as they were able to camp in the same manner as the soldiers and, in some measure, were able to be kept safe from calamitous events; others with more resources constructed more sheds and began to carry on with their occupations.

I cannot leave unrecorded the fact that some days after I had gone to the church to save as many precious items as I could, fire broke out there and burnt for three continuous days. The choir and organ were burnt, as well as the benches, a new image of the Virgen del Carmen (36), together with the locked chest in which it had been deposited; the image in question having been moved to the church by the Martines family and Phelipe Montovio in order to be placed in some chapel or other. The chests and vestments in the sacristy and also part of the sacristy itself were also burnt, as was one of the confessionals and all the woodwork in the main nave and almost all of that in the nave of the Virgen del Rosario (24).

A day or two before this fire occurred, as I was deeply concerned about all the sacred images that were set up in the church, and especially that of Our Lady of Europe, as it was so ancient and so famous, I sent the sacristan who was going into the city and also my brother-in-law, Joseph Serra, who used to go there every day, to save as many images as possible, especially that of Our Lady of Europe. But not being able to carry more than one of them, they brought this particular one and they were received with great joy by all the Roman Catholics of our congregation. It was also during those same days that the beautiful painted monument (37), depicting the mysteries of the Last Supper and the Holy Passion, caught fire and was burnt.

Having set up my tent which was very large and was almost like a palace in comparison to the constraints that I had experienced during the previous two weeks and being in a site far away from the shelling, my brother-in-law’s family and I moved in. But during the night-time, in fine weather, when it was thought that there might be attacks by the gunboats and the battery ships, which were the latest additions of the Spaniards, the tent would fill up with so many Roman Catholics who came to take refuge, that I found myself with less space than when I was staying in Xitxon’s (29) dwelling. Furthermore, the women being so timid by nature, made us all the more fearful, and there being a large convoy ready to sail to Mahon, His Excellency the Governor offered passages and provisions to all those women who wished to embark. This was also the case with those youngsters and inhabitants who wished to embark for Mahon or on another convoy sailing to London. Many men and women with their sons and daughters, Roman Catholics, Protestants and Jews, took advantage of this opportunity and embarked. Among these were all the English ministers with their families and also my assistant, Don Pedro María Raymundo, thus leaving me as the one and only priest with the small flock that remained, which numbered six hundred, more or less. My brother-in-law’s family also left, leaving us both on our own in our tent during the day, but not at night, when it filled up with people wanting to get away from danger.

More than a month had elapsed during which I had not been able to celebrate mass, due to the fact that I had not been able to have all the necessary sacred items together and also because the people were more concerned with finding adequate dwellings and in salvaging what they could from their homes. Furthermore, everything had been in disorder and confusion, and once things had calmed down, they began to call on me and plead with me to celebrate mass at least on Sundays and feast days. So, realising that people had this holy desire, I built a table as best as I could, and placing it in the plains of the Windmill Hill under a movable tent, as protection from the strong winds, and taking advantage of the privileges and regulations allowed me by my holy religion, began to celebrate mass there.

The very first mass that I celebrated in that tent was on the 13th May 1781. In this manner, I celebrated mass until June of that same year, because during this time I was able to set up a small shed beside my tent with access through it and prepared in it an altar with pictures and with the tabernacle that I had saved from the church. This was a very small tabernacle which had served, in ages past, as the container for the ciborium for the communion hosts and afterwards had been used for the Lignum Crucis (38) on the altar of el Rosario (24). I kept it well and properly arranged, with its yellow silk curtains, and I then transferred the reserved Blessed Sacrament from the temporary altar in Xitxon’s (29) dwelling, together with the ciborium, the vessels of holy oils for the sick, catechumens, the chrism and the Lignum Crucis (38). All these I placed in this sacristy which was kept locked, having first blessed the little chapel, assuming that I had the faculty to do so under Epikeia (39). I began to celebrate mass every day there and, as it was so limited in size, on Sundays and feast days I would set up the altar in the plains of Windmill Hill and in that manner was able to please all the faithful who attended.

Once we were more or less organised, as I have already explained, there were many discomforts experienced by the Roman Catholics in order to hear mass, because of the fierce winds that blew in the area and especially in winter. As the bombardment by the Spaniards had somewhat subsided, it was possible to venture into the city to collect some timbers and following the entreaties of the Roman Catholic inhabitants, my brother-in-law and I were persuaded to construct a large wooden hut. This, together with the cave and the tent, was able to accommodate almost all the Roman Catholic congregation, with each one of them agreeing to make themselves responsible to pay a certain amount of the cost. Thus, was this hut constructed and erected next to the tent, with the latter being dismantled and what had originally been the tent, was covered with wood and tiles and the end result was a substantial dwelling, large enough to celebrate mass under the rocky outcrop. Inside I placed the tabernacle and everything else, safe from bombs and shells, and set up an altar with its curtains and I began to celebrate mass in that place. Then I covered the hut with the sails that had been part of the tent, making it waterproof and protecting it from the wind, to the satisfaction of the Roman Catholic faithful. Furthermore, in order to better protect all the sacred items, I placed some barrels, one on top of the other full of earth, behind the altar to serve as a parapet, so that I could place myself and my bed behind the said barrels. In one of these barrels, seeing we had no chests, situated close to the altar, I placed all the church silver, in fact, the silver that I had actually saved. As there was such a multitude of people attending, some of them sat on the barrel and pressed the lid down into it and thus it remained, half opened, until my brother-in-law constructed a capacious chest in which I locked inside as many of the objects as I could. I left the larger items in the same barrel and filled it up with earth, therefore becoming the only witness to this secret, until the return of better times.

In this new and holy precinct, we carried out solemnly our sacrificial liturgy, as best as we could, including Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament and prayers, always asking God to concede whatever was best for the salvation of our souls and for His Greater Glory. During this period of time, from the beginning of summer and all through the winter months of that first year, I experienced much sadness, firstly because my sacristan had abandoned my side and had set up a small shop in the square of the New Mole with a Francis Carreras. He left me on my own and did not even come to serve mass, making it often very difficult for me to find anyone else who was willing to do so. Also, my brother-in-law, who had been my only consolation, following an illness, took an aversion to me, blaming me for the absence of his family. He kept bothering me continuously and when his illness worsened, he decided that he was no longer comfortable there and decided to go and live in Blectown (35). When he departed, I was left completely on my own, without anybody else, accompanied only by the fears experienced by those that await great rewards in heaven (40).

END NOTES

- Martí Crespo, Els Messa: del Raval al Penyal, Maó: Revista de Menorca, tom 91, Ateneu Científic, Literari i Artístic de Maó, 2012.

- Regarding the Minorcan community in Gibraltar, please consult Tito Benady’s article Los menorquines en Gibraltar en el siglo XVIII, Maó, Revista de Menorca, Ateneu Científic, Literari i Artístic de Maó, 1992; and the study by Martí Crespo awaiting publication.

- Charles Caruana, The Rock Under a Cloud, Silent Books, Cambridge, 1989, p. 31.

- The original document is located in the Diocesan Archive of Gibraltar, Primer of 1777-1805. Charles Caruana published an interpretation of the diary in English as appendix in his book The Rock Under a Cloud.

- The xebec (jabeque in Spanish) was a sailing ship, used in the Mediterranean, which had both lateen sails and oars for propulsion.

- This refers to the Spanish enclave of Ceuta on the north coast of Africa in the Strait of Gibraltar.

- John Raleigh was the governor’s secretary.

- General George Augustus Eliott, later 1st Baron Heathfield, was the Governor of Gibraltar.

- Mr. Davies was the Commissioner of Works.

- Capilla de los Hierros, now the Chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes.

- Altar of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad – Our Lady of Solitude.

- The Holy Name of Mary.

- South Port Gate.

- Irish Town.

- Main Street.

- This was a small square which existed at the time by Bedlam Barracks, now the site of Bedlam Court. The Barrack had previously been the Convent of the Poor Sisters of Saint Clare.

- This had previously been the Monastery of Our Lady of Ransom situated in the corner of the present Irish Town/Market Lane.

- Still popularly known as El Jardín de Green (or Glynn), it is located in the upper part of Lynch’s Lane. Colonel William Green was the Chief Engineer of Gibraltar during the Great Siege and had previously put forward the proposal for the setting up of the Soldier Artificer Company, formed on 6 March 1772, which became the predecessor of the Corps of the Royal Engineers.

- Captain Evelyn, engineer.

- Saint John the Evangelist’s feast day is celebrated on 27 December; Padre Messa might have been referring to the eve of the said feast day which would have been on the previous day.

- Mr. Boyd.

- Naval Commander.

- The original Spanish description of the event: ‘y algunos no llegaron a causa que les dieron fuego casi en medio de la badía’ is open to interpretation, as the words ‘dieron fuego’ can either mean ‘fired upon’ or ‘ignited’.

- Our Lady of the Rosary.

- A dogger was a ketch rigged boat traditionally used in the North Sea for fishing.

- Modern day Algeria.

- Ships transporting provisions.

- The British Consul, Mr. Logie, together with his wife and about twenty others, was expelled from Morocco and, after leaving Tangier, the whole group were escorted into Gibraltar Bay, where their schooner was moored at the entrance to the Palmones River. Here, near Puente Mayorga (hence Padre Messa’s reference to Lapuente), they remained virtual prisoners of the Spaniards until they were conducted to Gibraltar on 11 January 1781 (John Drinkwater, A History of the Late Siege of Gibraltar, London: T. Spilsbury, 1785, pp. 130-136).

- Chichon’s.

- Our Lady of Europe.

- The Governor’s residence – the Convent.

- Thomas Skinner, engineer. His wife, Mrs. Skinner, was purported to have been asked by the governor to fire the first shot of the siege from Green’s Lodge on 12 September 1779, while a military band, stationed nearby, struck up ‘Britons strike home’ (T. H. McGuffie, The Siege of Gibraltar 1779-1783, London: B. T. Batsford, p. 46).

- Windmill Hill.

- Hardy Town was a temporary settlement in the south end of the Rock established by many of the inhabitants fleeing from the bombardment. It was originally called New Jerusalem, but later got its name from that of the quartermaster who was put in charge. It was eventually abandoned and torn down after the siege ended.

- Black Town was yet another name for Hardy Town and came to be known as such due to the unhygienic conditions of the settlement.

- Our Lady of Mount Carmel.

- A retable or reredos consists of an ornamental panel behind an altar, usually in carved and gilded wood and containing images and paintings.

- Relic of the True Cross.

- Equity in Canon Law.

- This last sentence has been translated in a more literal sense but the meaning remains quite ambiguous given that a far less literal translation could suggest the following: “When he departed, I was left completely on my own, alone and fearful that someone may break-in and steal the church treasures”.

Translation and notes by Manolo Galliano

This article was first published in the Gibraltar Heritage Journal, vol 20 (2013).

Comments are closed