It should come as no surprise, in view of its position as a small British territory in the Iberian Peninsula, that over the last three centuries Gibraltar should, from time to time, have become a refuge for people fleeing conflicts on the other side of the border and beyond. With the outbreak of the French Revolution, for example, several members of the nobility arrived, as did people from the Campo de Gibraltar region shortly afterwards as a result of the Napoleonic invasion of the Peninsula. The constant conflict between Liberals and Absolutists in 19th Century Spain also gave rise from at various times to waves of refugees fleeing to the Rock as a first stage en route to the UK. In the 20th Century, the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) saw the arrival of numerous politically-committed people from both sides in the conflict. It is worth remembering, in this respect, that during the conflict there were two Spanish consulates on the Rock, one Republican and one Francoist.

A little earlier, in 1933, there was the peculiar case of the Mallorcan banker and smuggler Joan March i Ordinas, who illegally crossed the border with the Rock in his escape from Alcalá de Henares prison, as his first stop before temporary exile in Paris. More surprising still is the story, at the other ideological extreme, of the Catalan doctor and politician Francesc Dalmau i Norat. March and Dalmau represent two different sides of the coin of the flight to Gibraltar of those seeking refuge.

Dalmau was born in Girona on 24 July 1915 and grew up in a family culturally and politically committed to the ideals of Catalan nationalism: his father, the doctor and intellectual Laureà Dalmau i Pla, was an elected representative in the Parliament of Catalonia during the Second Republic; his mother, Laura Norat i Puig, was the daughter of the owners of Café Norat located on the Rambla in Girona. He began studying medicine at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and during that time co-founded the National Federation of Students of Catalonia and participated in the Events of 6 October 1934, for which he was imprisoned for a time.

When war broke out in 1936, he served as a volunteer doctor on several war fronts, which is why he had to go into exile in the south of France following the Republican defeat. But in July 1940, worried about how his mother and sister were, he decided to return to Girona. The authorities inevitably arrested him and he was initially imprisoned in the Castle of Sant Ferran in Figueres. Later he was transferred to prisons in Reus, Madrid and, finally, to Algeciras, where he was assigned to No 1 Punishment Battalion of Prisoner Soldiers at Punta Carnero.

A year after the ‘animalada’ (or ‘a silly thing to do’, as he himself described his attempt to return home) he began to fear that, among the miseries and hardships experienced every day in the punishment battalion, there was the additional danger that the Francoists wanted to use the prisoners as cannon fodder for the Third Reich. That is when he started to think about escaping.

But getting out of the concentration camp, making it to Catalonia without any money and continuing his escape towards the north was not viable at all. So, he turned his gaze toward the Rock on the horizon, a few kilometres from where he was, as a possible gateway to one of the most stable democracies of the time.

In the escape attempt nothing could be left to chance because any mistake could cost him his life. Therefore, taking advantage of his frequent permits to travel to the pharmacy in Algeciras, he began to take note of the area and even secretly contacted the authorities of the British office, which acted as a consulate, located in the town. The British agents assured him that, if he managed to reach Gibraltar, they would not repatriate him to Spain and he would be given protection. Carrying only a card from when he studied medicine in Montpellier as the only identity document, the time for him to make his move came on 27 September 1941. Taking advantage of a new permit to go to Algeciras, he managed to temporarily shake off the guard who escorted him and walked to Los Barrios, where he waited for sunset to enter the calm waters of the Bay. He described the scene in his biography Francesc Dalmau. From Normandy to Palamós (2016), written by the historian Francesc Marco i Palau: ‘I took off my clothes and, carrying only the documentation in a waterproof package, I began to swim slowly, until I found myself quite far away and swam more and more quickly, desperately, to the limit of my strength.’

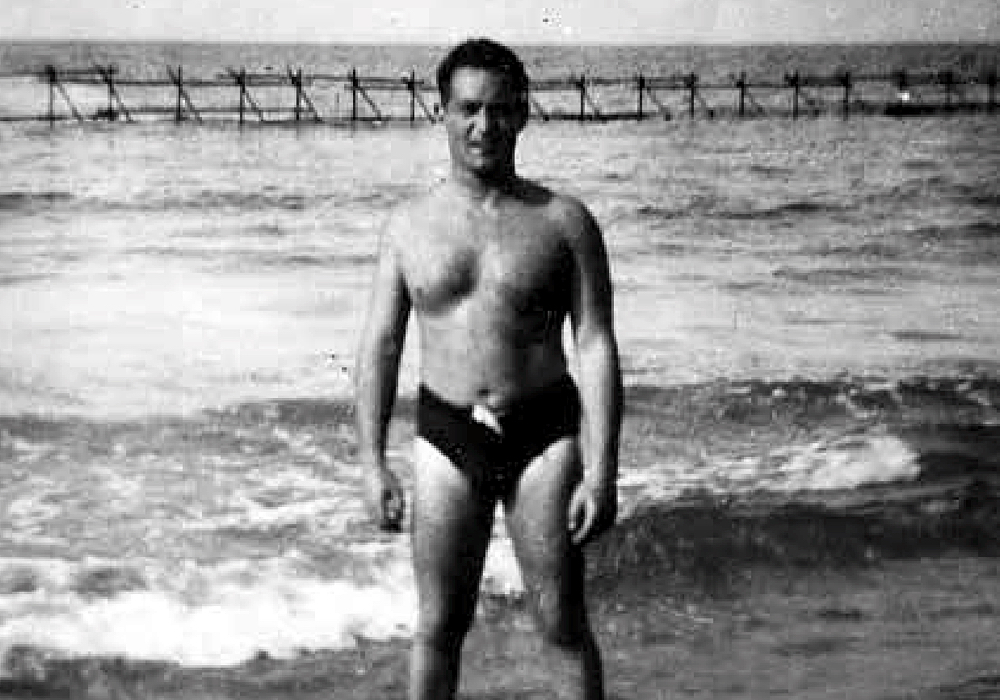

Arm over arm, stroke by stroke, stealthily, Dalmau approached the Rock without being detected by the coastal patrols of the Civil Guard. He was twenty-six years old, he was strong and he was used to swimming since he was a teenager at the Fosca beach in Palamós, where more than once he had reached the Formigues Islands and returned using a crawl stroke. He explained it himself in this audio: ‘I very carefully started to swim out, but under the water rather than on the surface, because it seemed to me that everyone would be able to see the splashes, until I got quite far out and, then, swimming slowly, very quietly, I saw that I had reached British waters. I had achieved my military objective. Success!’

After hours of moving through the water, he discovered a ship moored off Gibraltar and he climbed the mooring rope. It was an old, abandoned warship with no one on board. At one point, he saw a patrol vessel passing nearby and, despite signalling to it, it did not stop. It was not until the vessel had completed its patrol that it approached him and took him to dry land, free from the clutches of the dictatorship. He had put an end to a year and nearly three months of imprisonment in the Spanish concentration camps thanks to a Hollywood-style escape, followed by an eight-kilometre swim across the Bay. ‘You have to bear in mind that I arrived there in swimming trunks, knowing almost no English at that time and without so much as five Spanish cents in my pockets.’

The local authorities put him in a cell, where he was visited by officers of the immigration department and was interrogated by the security services to check his identity and his background. “I told them that I wanted to join the British army because fighting Hitler was the way to continue fighting Franco, because at that time only the United Kingdom was confronting Nazism.” As soon as he was freed, he asked to set sail to the United Kingdom, following the same route, with the stopover in Gibraltar, that other Catalans such as Jornet J. Llonchs and Josep Vaquer had followed. Getting to Bristol was to take a while because first his ship had to cross to Canada to join a convoy. As soon as he set foot in the UK, which at the time was under heavy attack from the Nazis, Dalmau became convinced he ought to sign up to the British Army. On 27 October 1941, he joined up not as a doctor, but as a private, and the next day he was posted to the Pioneer Corps, an auxiliary support unit that also acted as a corps of engineers. Within this unit was the Number One Spanish Company (NOSC), a company made up mostly of Republicans from the French Foreign Legion that had already fought on the Norwegian front and alongside which he fought in the decisive Allied invasion of Normandy, but no on D-Day at H-hour (6 June 1944).

After the war, with four medals on his chest, Dalmau returned to Montpellier to finish his studies in medicine and kept up contacts with the Generalitat, the Catalan Government, in exile. By the mid-1950s, no longer afraid of reprisals, he returned to Catalonia and married Rosa Maria i Oriol. He worked as a family doctor in Breda, Palafrugell and Palamós, where he lived the rest of his life and was actively involved in the clandestine anti-Franco struggle. After Franco’s death, he was elected – like his father half a century earlier – as a deputy to the Parliament of Catalonia for the political party ERC in the 1980 elections. From 1983 to 1985 he was also mayor of Palamós, which appointed him as an ‘adopted son’ of the town in 2001 and where a square (with a plaque) bears his name. Francisco Dalmau died shortly afterwards, on 30 December 2003.

Article published on 23 January 2024. Translated by Brian Porro

Photographs courtesy of his biography Francesc Dalmau. From Normandy to Palamós

Comments are closed